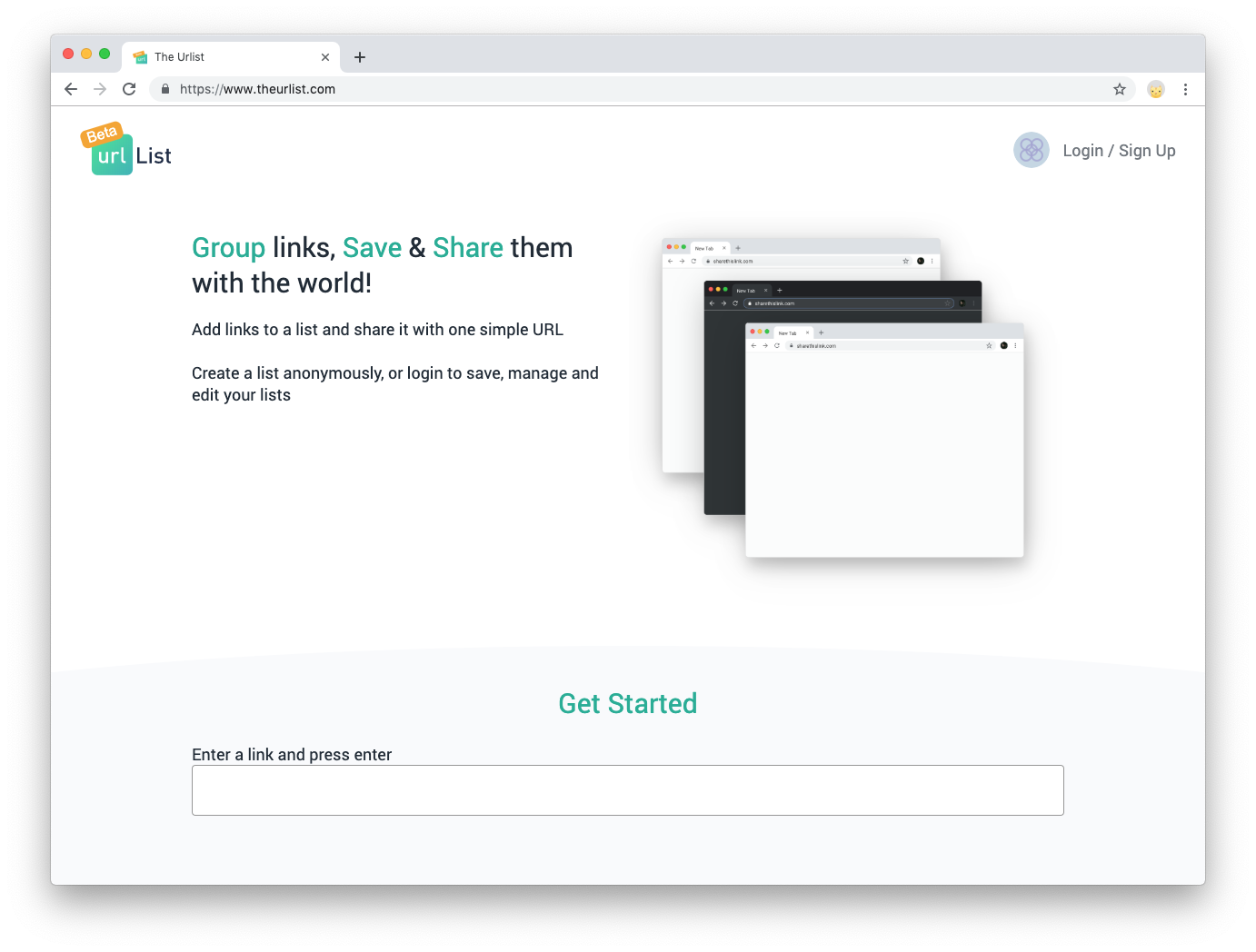

Today we are pleased to announce that we (Burke Holland and Cecil Phillip) are releasing a project called “The Urlist”. You can access it starting today at theurlist.com.

The Urlist is an application that lets you create lists of url’s that you can share with others. Get it? A list of URL’s? The Urlist? Listen, naming things is hard and all the good domains are already taken.

This project was born out of a realization that I was ending my presentations with a slide full of links to additional resources. That’s crazy! What exactly is the audience supposed to do with that? Take a picture with their phone and then go back and manually type it all in later? What decade is this!?

What I wanted was one, easy to remember URL that would point to the full list of resources from my session. I was surprised when I found that there weren’t a lot of options out there for doing this.

So I enlisted the help of my friend Cecil Phillip and over the past several months we’ve been steadily working on this project. We debuted it last week at Microsoft BUILD 2019, and today we’re making it available to everyone.

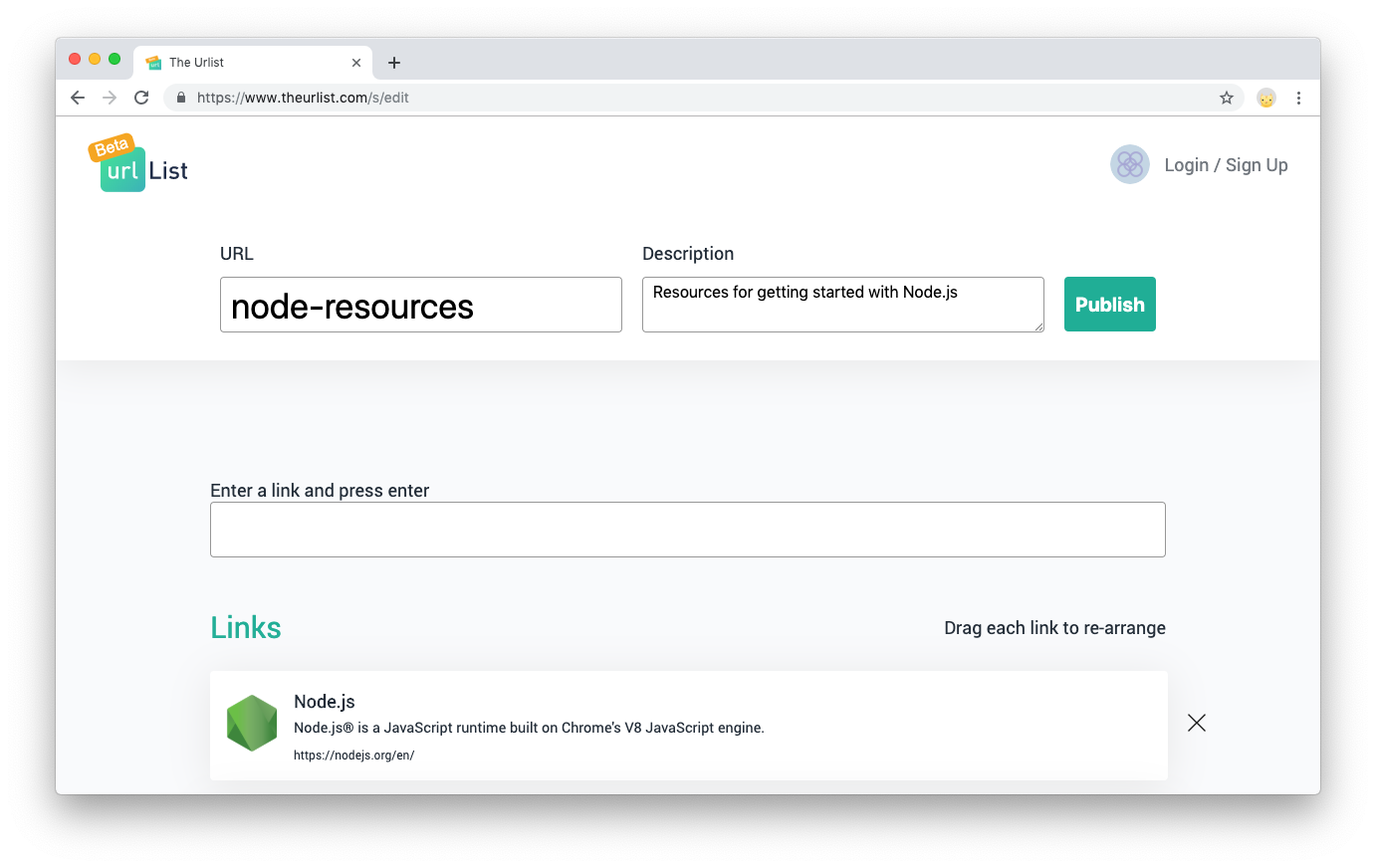

The app is pretty simple — you just start adding links that you want to group together. The app uses the Open Graph information on the site to get a title and description for your link automatically.

You can give your list a custom url and a description. If you don’t select a custom url, it generates one for you. When you click publish, you get a URL that points directly to all of your links. That’s it! Think of it like bit.ly, but for a bunch of links.

You don’t have to log in, but if you do, you can publish and then go back and manage your lists. Otherwise, your list is created anonymously and once you publish it, it’s final. Right now we only support Twitter login.

We had a dual motive in building this application. While we were trying to solve a problem, we were also trying to learn how to build a truly serverless application on Azure. And we wanted a real-world use case — not a contrived example that served no actual purpose. That’s why this entire project is open source.

Frontend: Vue + TypeScript

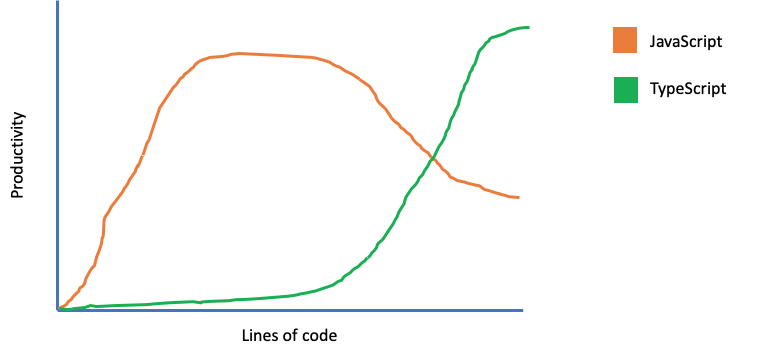

The frontend is a single page app written with Vue and TypeScript. I specifically chose those two technologies because TypeScript is becoming astonishingly popular, and I wanted to see what the experience would be like with Vue.

There’s a lot to unpack in that experience, but suffice to say that it was insightful.

Having done it, I don’t think I’m sold on the value of TypeScript for a project of this size. Strong typing is a tax. You pay the tax in exchange for better maintainability and tooling, but in a project of this size, there simply isn’t enough scale to justify the expense. I feel like there is an intersection between the lines of code in a project and when TypeScript becomes valuable. I just never reached that intersection in this project.

It’s not a great chart — I know. I made it in PowerPoint.

It’s not a great chart — I know. I made it in PowerPoint.

There is also the issue of the extensive ecosystem of Vue components, many of which do not already have typings. That leaves you in a spot where it feels like you have to coerce TypeScript into doing things that it doesn’t want to do. You end up writing “any” and “declare” a whole lot, which is basically like screaming, “LOOK AWAY, TYPESCRIPT!”

While on the subject of Vue Components, we used a few in this app that I think are just wonderful.

We used the Vue Modal component for…..…..modals.

We used the SlickSort component for drag and drop sorting. This component is really cool. I like it a lot and I have no idea how it works, but it works. It even works on mobile.

And Vuelidate for validation — including async validation that requires us to check with the API to see if a chosen url is available.

The frontend is hosted on Azure Storage. This is partly why we call it “Serverless”. Since Vue apps compile down to just static HTML, CSS, JavaScript and Image files, we can just host it on Azure Storage.

It’s “Serverless” because it scales indefinitely and we only pay for what we use. In the case of Azure Storage, we pay $0.0184 per GB. The size of our entire dist folder — images and all is 1.8 MB.

We also pay for bandwidth usage here. It costs us 8 cents per GB, but the first 5 GB every month are free. So our application has to see solid usage before we pay anything at all for bandwidth.

Azure Storage is definitely the best way to host static sites. It’s got no overhead and it’s crazy fast. There is no container to startup. No Node server to run. You just…..can’t beat this type of hosting for single page apps.

Backend: Azure Functions + Dotnet Core

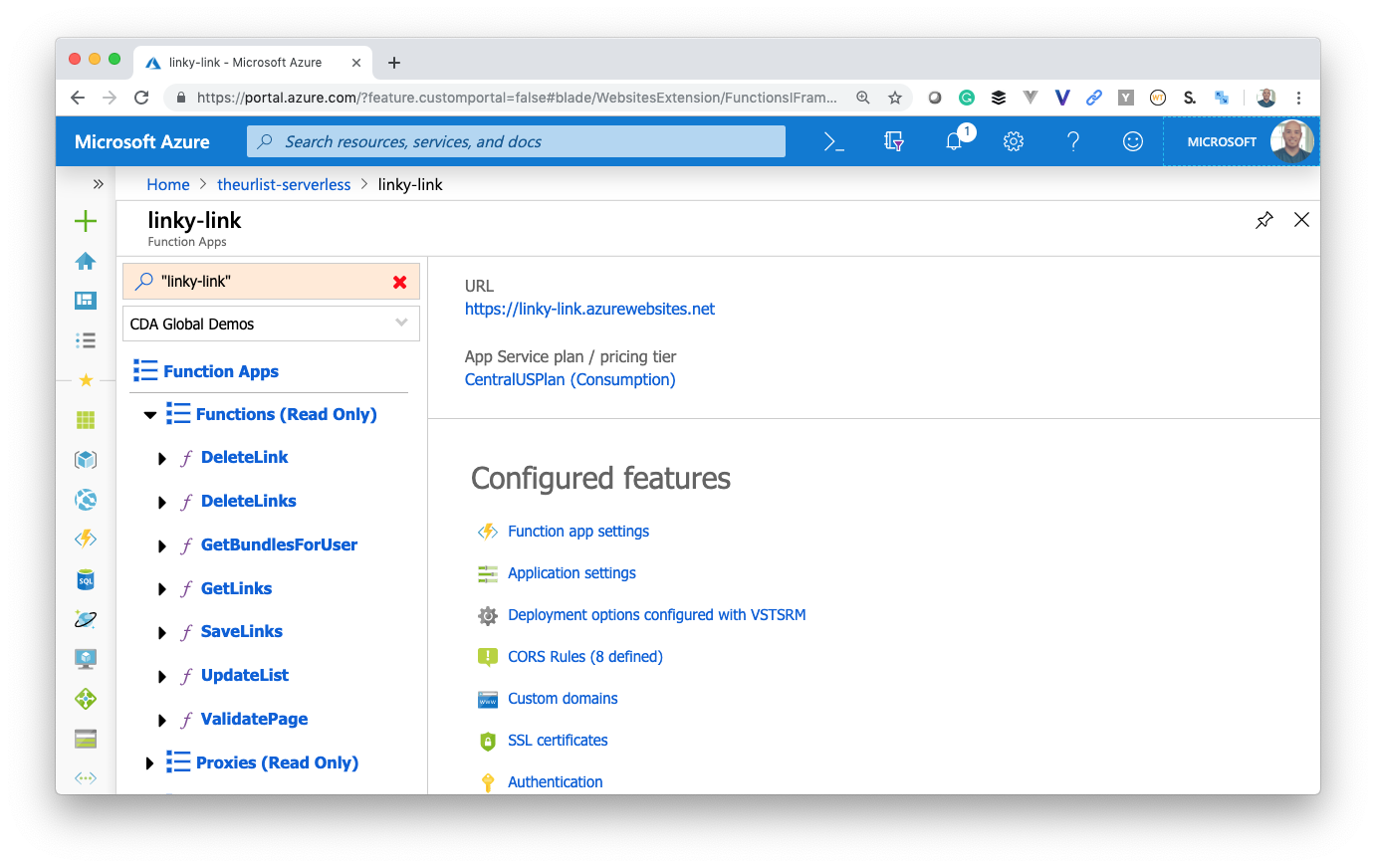

Cecil wrote the API with C# using Azure Functions. Functions is what we typically think of when someone says “serverless”. It’s the product that Microsoft positions for that market and probably falls more in line with what’s in your head when someone drops that word at a dinner party.

We chose to build the API in C# because we wanted to mix and match technologies like you might out in a real-world application. We could have had a JavaScript stack through and through, but working across technologies gave us both a chance to widen our horizons.

Each API endpoint has a corresponding Function. Cecil named those Functions so it’s relatively easy to figure out what they do just by looking at the names.

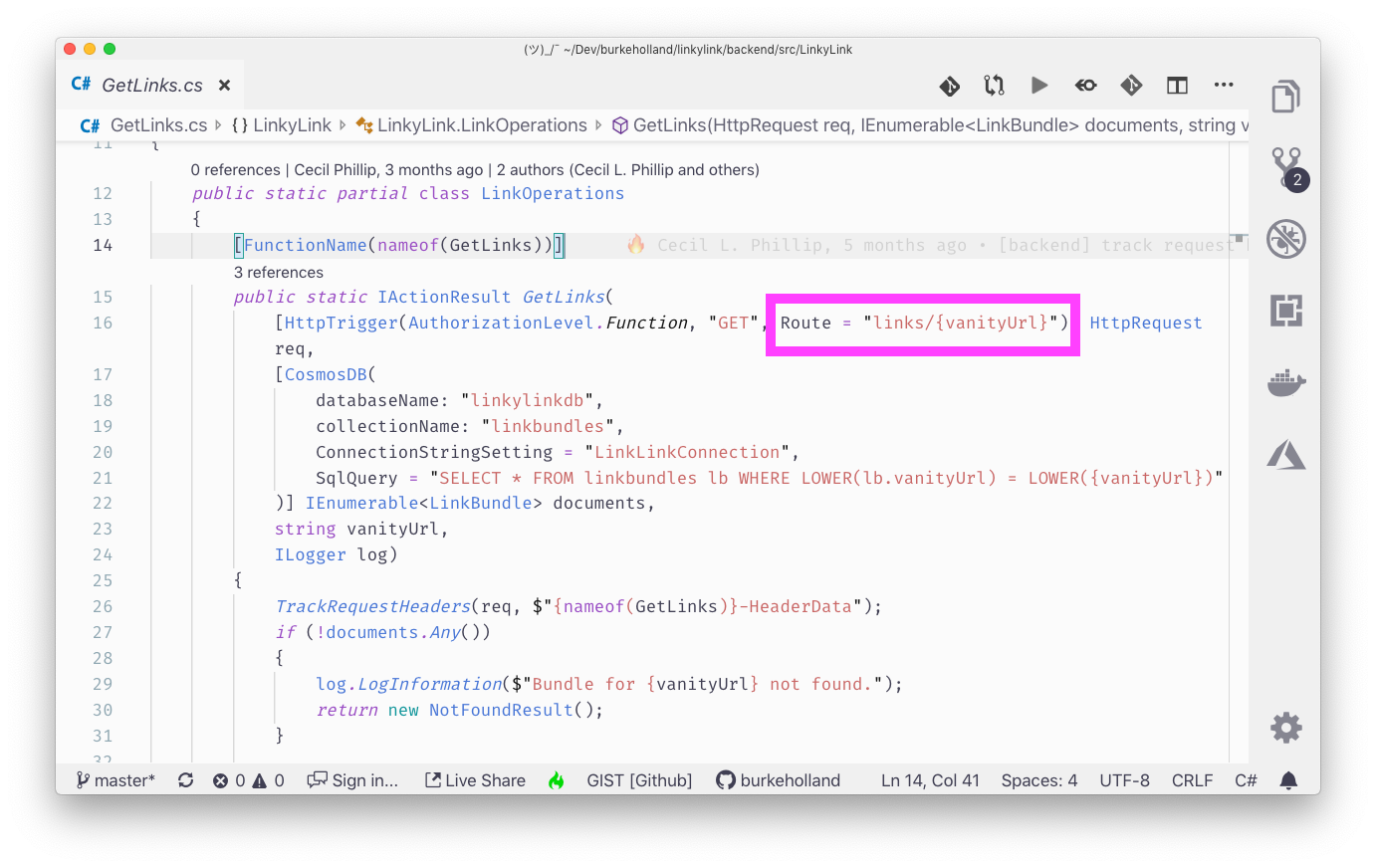

He used the built-in routing capability in Azure Functions to make them RESTful endpoints. The beauty of this is that when you are working on the methods, they make sense to humans. When you are consuming them, they make sense as an API.

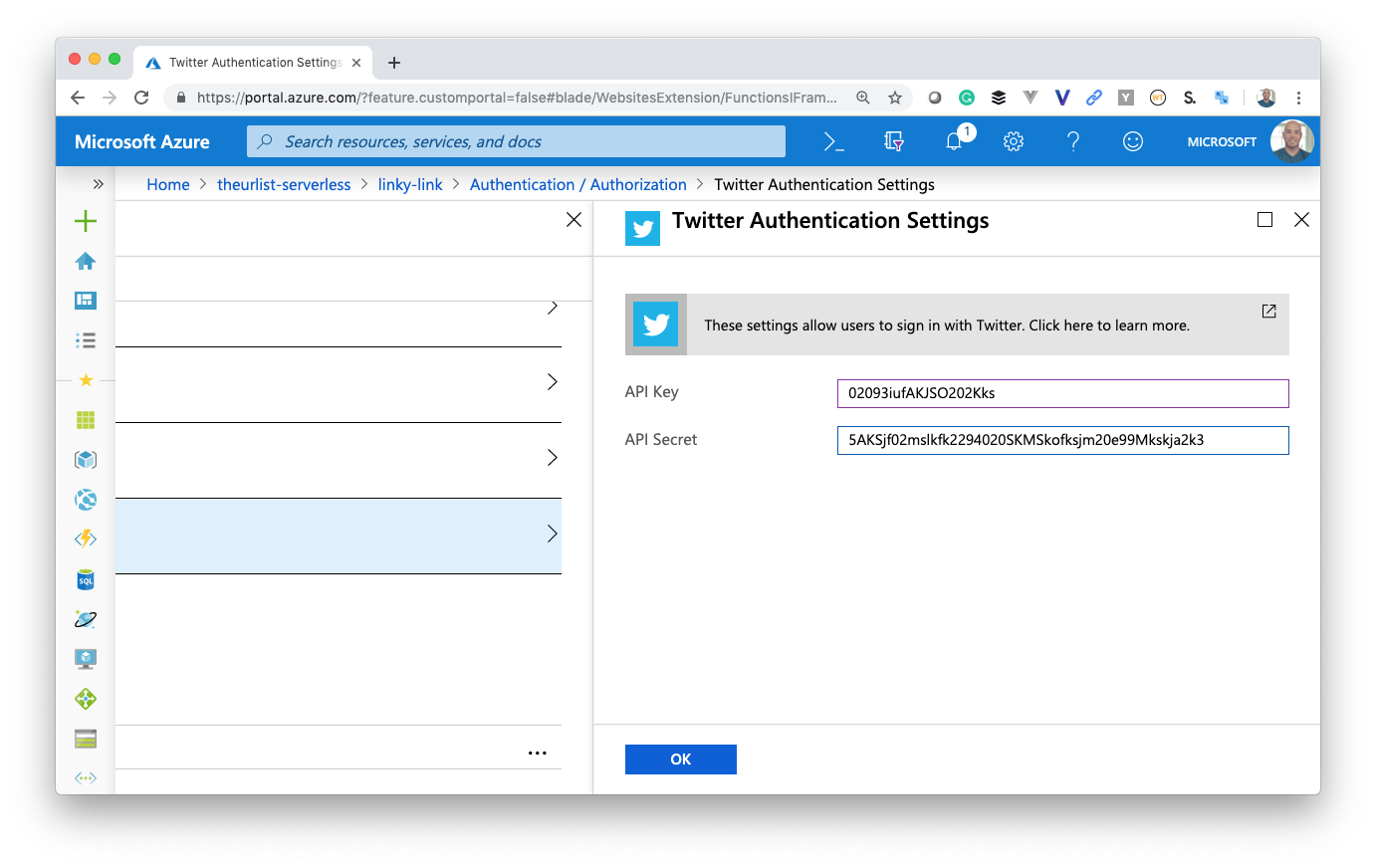

We also used the built-in authentication mechanism that Functions exposes via Azure’s AppService Authentication. We chose to do a social login only since we didn’t see a need to store usernames and passwords. On Cecil’s end, he followed the instructions in the “Authentication” section of the Azure Portal for our Functions app to set up a new application in Twitter and then copied the keys over.

Relax, these aren’t our actual keys

Relax, these aren’t our actual keys

This lights up the /.auth endpoints in our Function app. We can now call these endpoints from our frontend and it will direct the user through the auth flow. For instance, if we want to log them in and then redirect them back to the application, we just have our “Log In” button go to this URL…

https://www.theurlist.com/.auth/login/twitter?post_login_redirect_url=https://www.theurlist.com

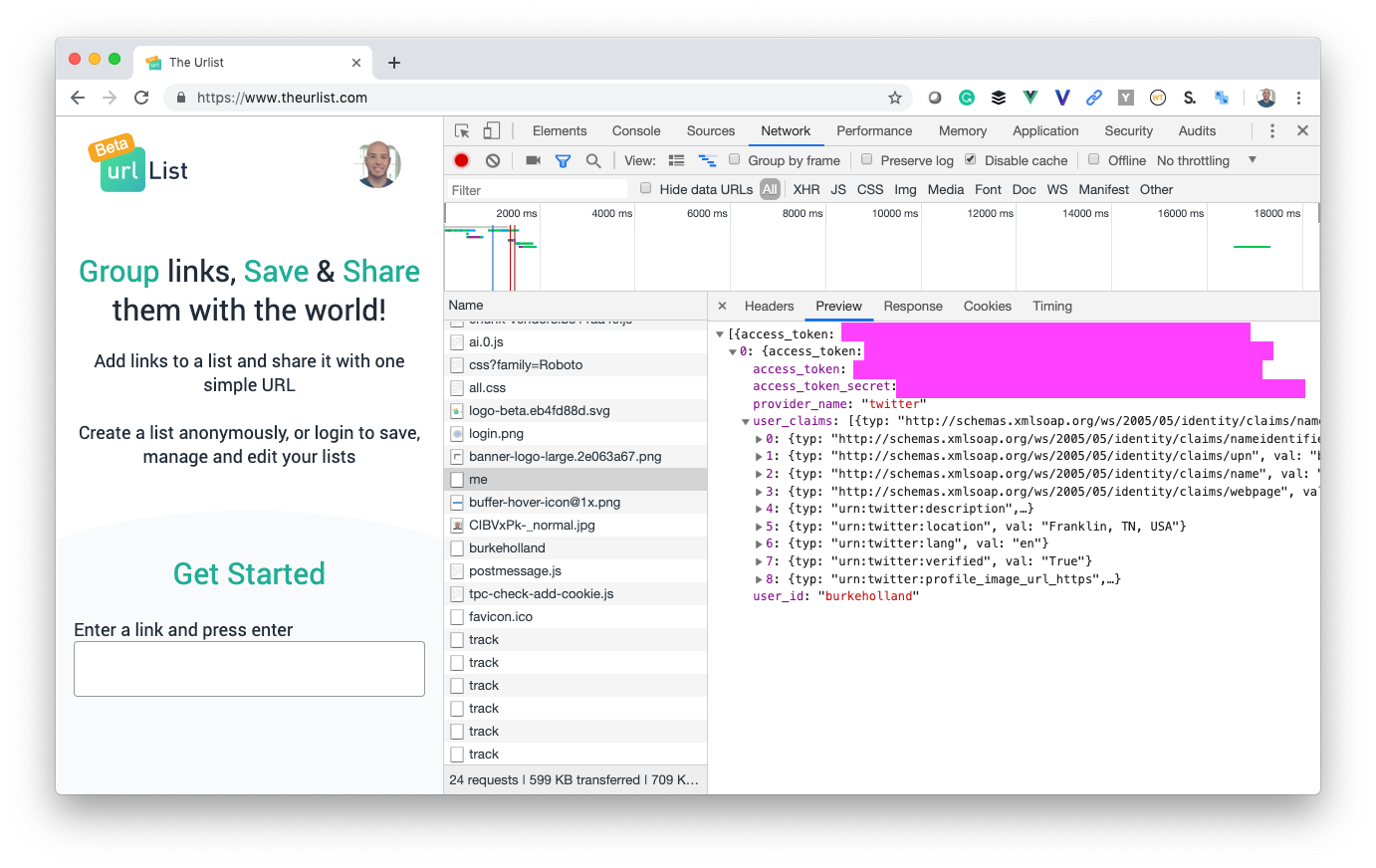

This sends the user over to Twitter to authenticate, and then back to our application. When they come back, they now have an auth cookie attached to their session. We can see that if we look at the cookies in the dev tools.

Now we can ask for information that Twitter has on the user. These are things like username, full name, avatar — ect. We do that by calling the “me” endpoint that got lit up automatically when we turned on authentication.

https://www.theurlist.com/.auth/me

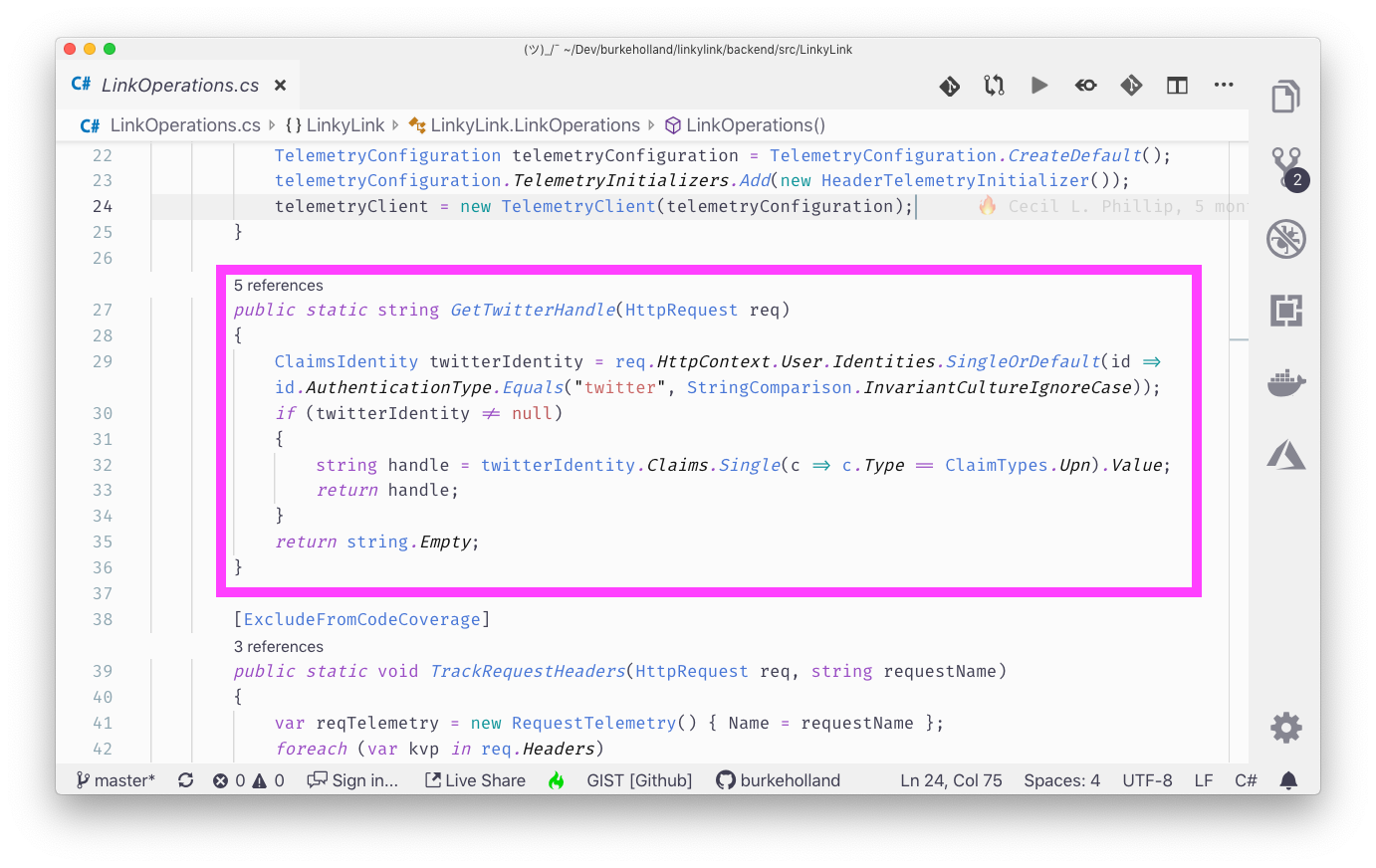

And Cecil can now validate every request I make to the API from the frontend and get the same user information. This is how we figure out what lists are yours, and whether or not you have the right to edit them.

Cosmos DB + SQL API

For our data store, we used Cosmos DB and the SQL API. This allowed us to have a NoSQL data store that we could still query with SQL. I find that NoSQL is great until you need to do something beyond just a trivial query. Then everything starts to feel like chaos to me and I think of this slide from James Mickens “Computers are a sadness, I am the cure”.

There’s also a nifty Cosmos DB extension for VS Code which makes it quite a bit easier to work with our documents and actually see the database. Azure Cosmos DB - Visual Studio Marketplace Get it now.marketplace.visualstudio.com

There is just no substitute for being able to see your database when you are starting from the ground up. Being able to see it within VS Code is even better.

Cosmos DB is one spot where our application is not, strictly speaking, serverless.

Cosmos DB runs us ~25$ per month which gets us 100 RU’s, or “Request Units per Second”. We have to buy those up front each month, and even if we don’t use all that, we still pay for it. We are also capped there, so if our application gets super popular, we have to manually scale out by reserving more RU’s.

Azure Front Door

We use Azure Front Door to glue the frontend and the backend together. Here’s what I mean by that…

Our frontend runs on Azure Storage and its URL is https://theurlistdotcom.z19.web.core.windows.net/

Our backend runs on Azure Functions and its URL is https://linky-link.azurewebsites.net/api.

What we wanted was to have one domain — theurlist.com. We wanted the root to point to our Vue app, and /api to point to our API.

To pull this off, we used a new product called Azure Front Door.

Front Door bills itself as a tool for “highly available global applications”.

In our case, we were less interested in that and more interested in it’s ability to let us stand up an entry point for our application and organize all of the pieces behind that single point of entry.

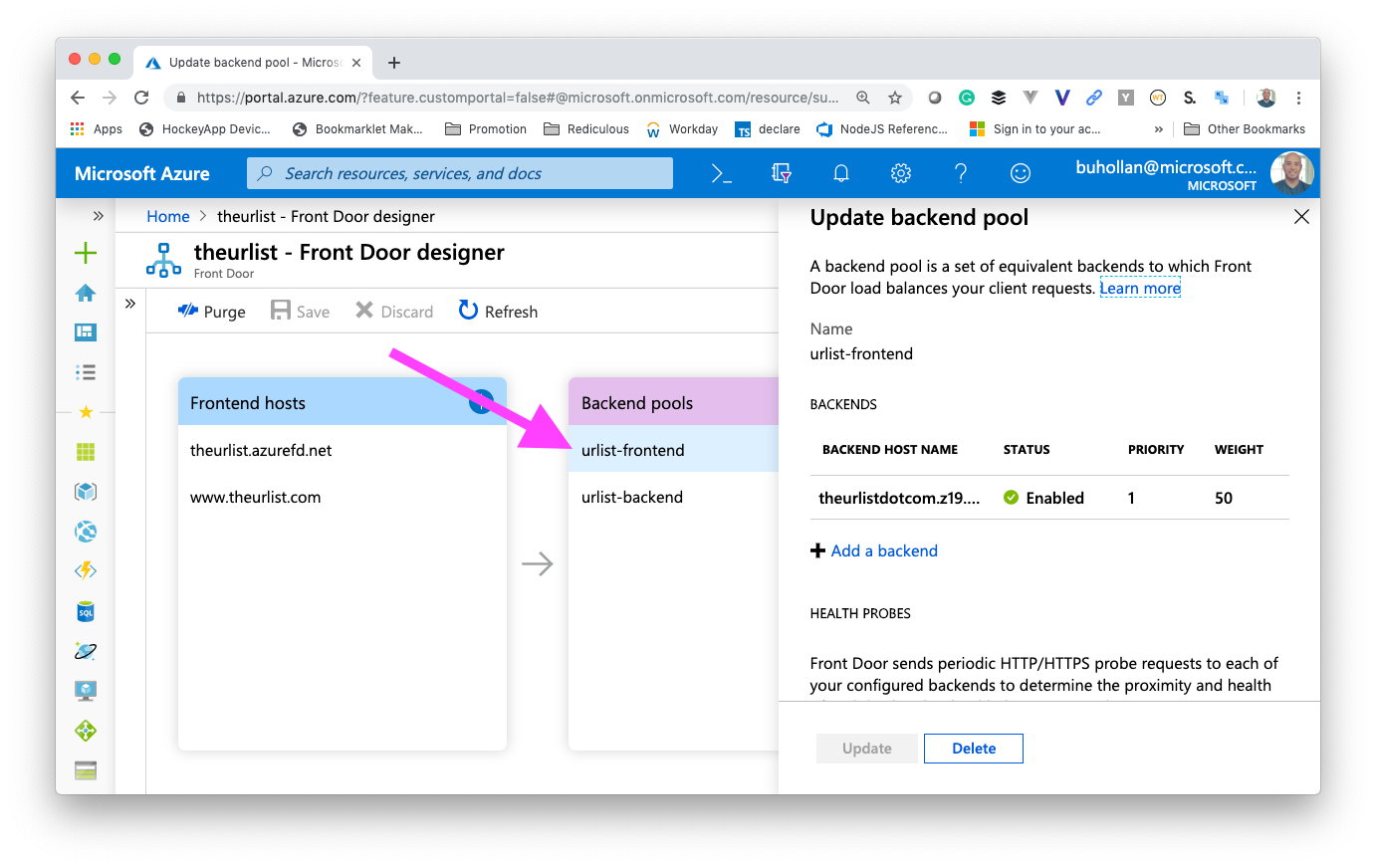

Front Door works via a visual designer interface. It starts off by giving you a “Frontend Host”. By default you get…

It then wants you to identify “Backend Pools”. These are just the resources that you want to direct traffic to. For us, that’s the static site on the frontend, and the Functions app on the backend. I’ve just called mine “urlist-frontend” and “urlist-backend”. If you look inside them, they point to Storage and Functions respectively.

Last, we have the routes that we want to define.

In our case, we have four routes…

-

The root of our site, which points to urlist-frontend in our “Backend pools”

-

/api which points to urlist-backend in our “Backend pools”

-

/.auth which points to urlist-backend in our “Backend pools”

-

A route which redirects all http traffic to https

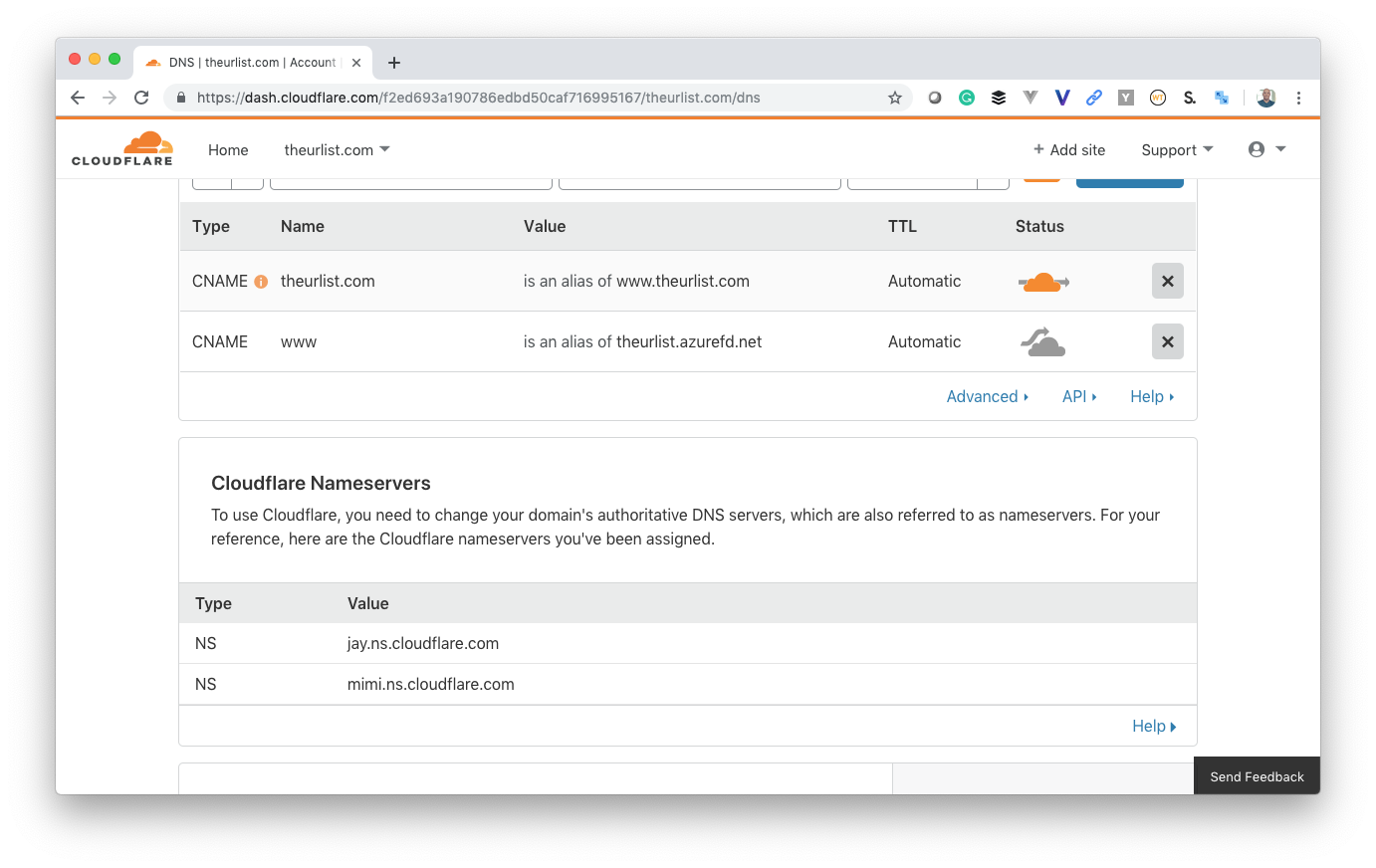

Our custom domain gets added to the “Frontend hosts” section. We add a new domain by pointing to theurlist.azurefd.net with a www CNAME in our DNS. Front Door then verifies that is the case, and magically creates and assigns us an SSL certificate for www.theurlist.com. Not having to configure SSL was….kind of amazing.

Front Door also acts as a CDN for our app. It’s just sort of built-in to the product. That means that we are cached at the edge around the globe which just increases the speed at which we can get the app into people’s browsers.

Solving The A Record Problem

The last thing we had to do was figure out how to get Azure Front Door behind an A record.

When you stand up a custom domain, you need to give it an A record. This is often called a “naked domain”. It’s just the domain, without www. In our case, that’s theurlist.com. The problem is that A records have to be an IP address, and Front Door doesn’t give us an IP. It only gives us that theurlist.azurefd.net.

To solve this, we decided to simply redirect any traffic coming to theurlist.com over to www.theurlist.com.

I registered the domain with NameCheap, but I was unable to get their redirect rules to reliably work. In the end, we stood up a Cloudflare instance as our DNS. Cloudflare allows us to create a CNAME for the root (@) and point it at www.theurlist.com. Now we already said you can’t do this — and you can’t according to the DNS spec. But Cloudflare allows it with something called “CNAME Flattening”.

CNAME Flattening

When you create a CNAME and point it at the root, Cloudflare basically resolves the IP of theurlist.azurefd.net and that’s what get’s returned as the A record. The problem is that in the case of Front Door, we can’t go directly to the IP, because the IP is the load balancer. It doesn’t know which site we want if we just navigate to the IP.

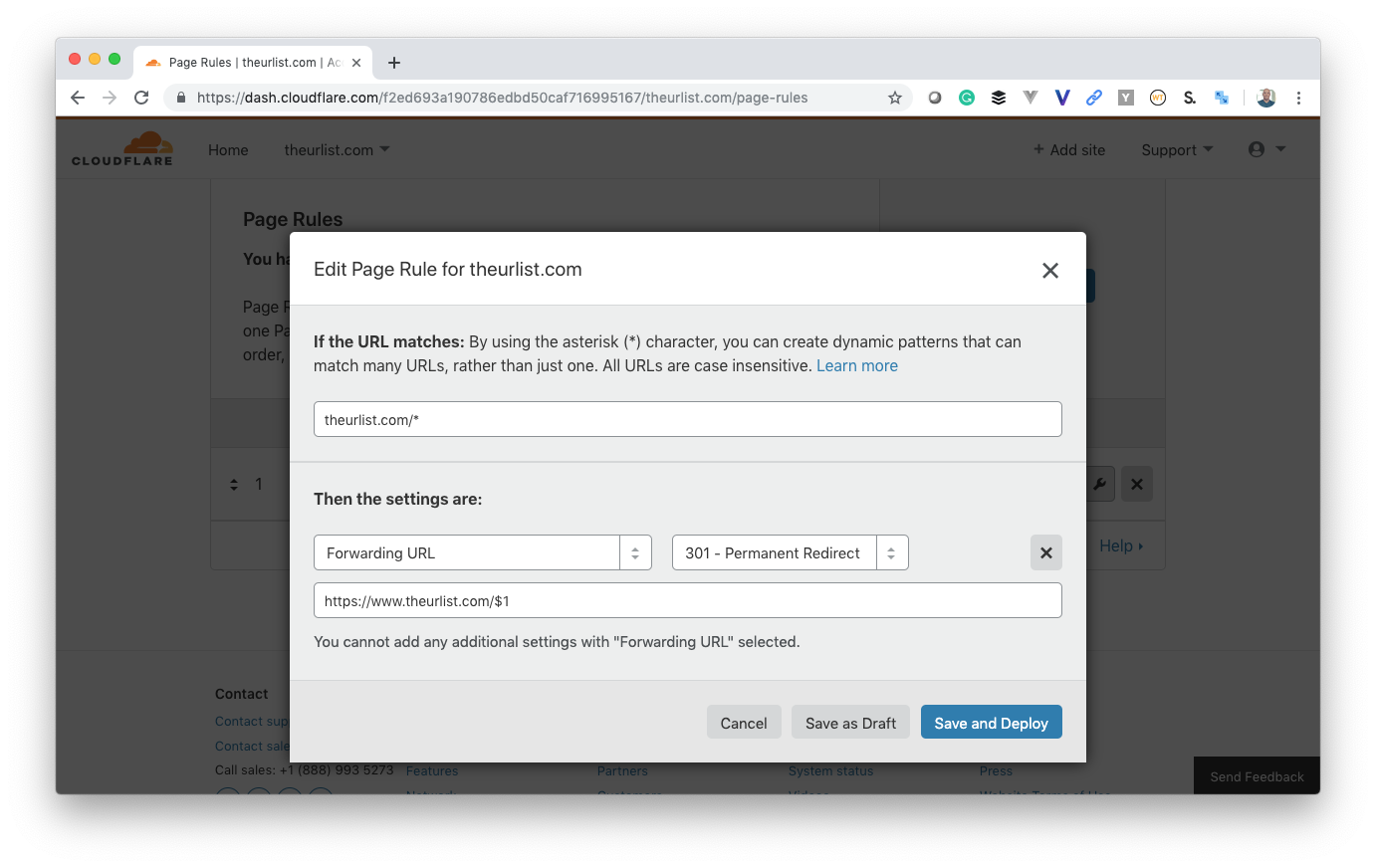

Since we are already going through Cloudflare to resolve our domain, we can add a page rule in Cloudflare to capture all traffic and redirect it. That orange cloud in the image above indicates that traffic flows through Cloudflare’s HTTP proxy. That’s how we can capture it and redirect it with a page rule.

It took me a while to figure out what I had to use a *in my path to capture the rest of the path, and then a $1 in the redirect to pass it through.

This gives us a naked domain without needing an IP address. Ship it.

Azure Front Door is priced by route. The first five routes cost $21 total. Outside of that, it is consumption based at around 25 cents per GB transferred. There is a little up-front cost here, but we get a lot more with Front Door than just an endpoint…

-

SSL

-

CDN

-

Global HTTP balancing

-

Application acceleration

-

System health monitoring

Share the internet

I came up with that tag line myself. Do you like it? Should I go on Shark Tank? Are we going to IPO this year?

We think this application is interesting not just because it shows how we would build a web application, but also because we think that the way we’ve leveraged Azure provides the maximum amount of speed and scale for the dollar.

If you’re interested, you can check out Build 2019 session on The Urlist called, “The good, the bad and the ugly of serverless”.

We hope that this application is useful for you not just from a code and architecture standpoint, but also as an actual application that you can use to share your links. We’d love to see your issues and PR’s!