A wise man once said this about Serverless…

So wise! So profound. So obnoxiously vain to use your own quote.

“Serverless”, is a buzzword. We can’t seem to agree on what it actaully means, so it ends up meaning nothing at all. Much like “cloud” or “dynamic” or “synergy”. You just wait for the right time in a meeting to drop it, walk to the board and draw a Venn Diagram, and then just sit back and wait for your well-deserved promotion.

A lot of very smart people have tried to define the word in a meaningful way. Here’s one that you might have seen before..

Build applications without thinking about servers

I actually think this is pretty good at answering the “Wait! How can there be no server!!?!?!” question. But I think this definition falls a tad on the naive side.

Nobody really thinks about servers when they are writing their code. I mean, I doubt any developer has ever thrown up their hands and said “Whoa, whoa, whoa. Wait just a minute. We’re not declaring any variables in this joint until I know what server we’re going to be running this on.” Or maybe you do. I have never ever done that. I always do it AFTER I’ve written the application. Come to think of it, maybe that explains a lot.

But besides, isn’t that the whole point of a Platform as a Service (PaaS)? Don’t services like Azure and Heroku and a host of others already enable you to deploy your code without knowing anything about the physical server where it’s running? Haven’t we solved this problem?

And if all of that is true, it seems to me that nearly everything in the cloud that is an “as a Service” product would be Serverless. Which means it would be easier to assume that everything is “Serverless” and just try to identify when something is not. I don’t even know what we could call that. Serverfull? Server as a Service? I know! VIRTUAL MACHINES.

I don’t think you can explain Serverless in one sentence. This is because Serverless isn’t a single concept. It’s really 3 concepts that are used together to create a new type of cloud service. So don’t feel bad if your pug doesn’t get it when you try to break it down. It’s not your fault and a pug is a dog. I’m relatively sure that mine forgets nearly everything every 24 hours. Every day I tell it to get off the couch and it acts like it’s never heard this information before.

Let’s look at the 3 properties that a technology must exhibit to be considered Serverless. These are the “Laws of Serverless”.

Law of Furthest Abstraction

The “Law of Furthest Abstraction” says that you have no knowledge of the underlying system where your code runs.

This is different from a PaaS. A PaaS hides the operating system, but you still need to know about the runtime and you still need to have some system knowledge.

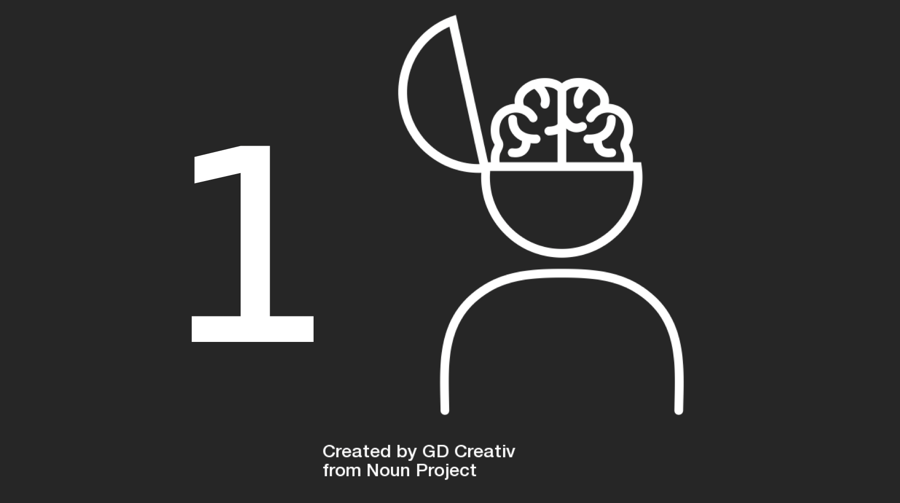

For instance, Azure’s PaaS is called “App Service”. When you create an App Service instance, you need to tell it what sort of App Service Plan you want to use. That service plan defines how much memory and CPU your instance will receive. For instance, here’s what the B (Basic) tier App Service Plans look like…

This means App Service is not Serverless.

A service in Azure that is Serverless would be Azure Functions. Azure Functions has no concept of App Service Plans. You run your code in Azure Functions and it will receive all the computing power that it needs when it needs it. It’s up to Azure Functions to figure that out.

How does that even work?!?

It works becdause of the second law of Serverless: The Law of Inherent Scale.

The Law of Inherent Scale

The Law of Inherent Scale says that scaling is an intrinsic attribute of the technology; so much so that it just happens automatically.

With Azure Functions, scaling just occurs. And remember, scaling is both out and back. It’s not enough to be able to scale out, the service needs to also be able to scale back; all the way to zero. That last part is important as you’ll see when we get to the third and final law.

The way that Azure Functions accomplishes this is by adding servers as your demand spikes, and removing them as the demand subsides. This includes putting your app back on cold disk if it hasn’t been called for a period of time. It then has to rehydrate the application when the next invocation occurs.

You can actually watch this happen in realtime by simulating some load on an Azure Functions instance. Watch the GIF below and you can see the number of servers increase as the CPU gets pegged.

.

.

What about a PaaS though? Don’t most PaaS’s scale?

Yes, They do.

Let’s look at Azure App Service again as an example. App Service can scale out in one of two ways. One way is for you to manually add another App Service instance (B tier for example). This would not be considered “inherent scale” since it does not happen automatically.

The second way is something called “Auto scaling”. This is where Azure will automatically add new App Service instances for you as the load increases. That is inherent scale. However, you have to scale in chunks - or rather by adding full App Service Plan instances. In other words, you have to add another full B instance to scale out, even if you don’t need the entire amount of that compute. This means that you are paying for compute whether you use it or not. This brings us to the third and final Serverless Law - the “Law of Least Consumption”.

Law of Least Consumption

The Law of Least Consumption says that you only pay for what you use. Coincidentally, this also everyone’s most favorite law. Money talks. But it doesn’t buy happiness. But it does buy jetski’s and I’ve never seen an unhappy person on a jetski.

.

.

Think about it like this: in your house, or your parents house, or apartment or wherever you happen to live, you probably have running water. But that water doesn’t run all the time. It only runs when you need it. You turn the faucet on to get water, and off when you aren’t using it. By the way, you can now get a faucet that is controlled by Alexa. Which is just what we need - robots in charge of the water supply.

Azure Functions is like a water faucet for compute. You only get charged for what you use. That occurs in a few different ways…

- Code storage - you pay for the disk space that your code actually occupies on the server

- Executions - you pay per execution of your function

- Execution time - you pay for the amount of compute that your function uses.

You also receive 1 million free executions a month. That combined with the miniscule cost of storage means that if your Azure Functions don’t get called, you don’t pay anything. This makes a lot of a sense as a customer. Just think of all the compute that we have paid for and wasted all these years! You could be retired already! But probably not because you’d blow all that extra money on jetski’s.

The cloud can (and should) save us money by being able to target compute by need and not just allocating it in “use it or lose it” buckets.

Applying the Serverless Laws

Now that I have established an irrefutable framework to determine if something is Serverless, we can apply these laws to any technology to determine if it is or is NOT Serverless.

Azure Services that are Serverless

- Azure Static Sites

- Logic Apps

- Cosmos DB

- Note - Cosmos DB isn’t quite Serverless just yet, but it’s close. It conforms to law 1, but up until recently, you’ve had to buy database bandwidth in chunks which means it did not conform to laws 2 and 3. However, as of Ignite, the team announced “Auto Pilot”. This is a feature which automatically adds throughput as the load requires it, but you still have to pay for a basic allocation. Once Cosmos DB allows you to start from absolute zero, it will comply with all 3 laws and can be considered “Serverless”.

- SQL Server

- Believe it or not, SQL Server has a “Serverless” offering.

The next time someone casually throws out a “Serverless”, see if satisfies the 3 Laws of Serverless. If it does, you can save yourself a “well, actually”. If it doesn’t, just nod and smile. And try to pay attention to the Venn Diagram.